~ This post was also published at Psychology Today as part of the series The Everyday Unconscious: How The Mind Works When We Are Not Looking

Maybe you have seen the Facebook meme, reading “If you don’t take care of your mental health now, you will be forced to deal with physical illness later.” Perhaps you even thought “Hmm…” before hurriedly scrolling down to the videos of baby goats in pajamas (they are glorious!). We don’t want to think of our physical health until we are forced to, but we are often even less likely to admit that mental health matters too. When I first saw that meme, I thought “Thanks for nothing, Renѐ Descartes!” and here is why.

Did you ever wonder about why in today’s society we think of mental and physical health as separate? This dualism is not some mathematics theorem that conveys an absolute truth. Yet, few have probably even questioned it, not because we are unintelligent or complacent, but because, as we grow, we implicitly learn to live by sets of rules and contracts that govern society. Some are explicit, like how a green light means “go” while a red light means “stop.” Others are more obscure and, whether you realize it or not, may follow from old philosophical traditions that influenced the formation of our society.

Cartesian Dualism

The mind/body duality is one such legacy and it started with Renѐ Descartes. Famous for his Cogito Ergo Sum (I think, therefore I am), Descartes struggled to reconcile religion with the newly developing and gaining in popularity sciences. Unlike many philosophers of his time, he argued that we cannot trust our senses to arrive at absolute truths, because our senses can be misleading. The only thing Descartes deemed undoubtedly absolute was awareness or thought. But since the senses could not be trusted, thought had to be completely divorced from the body. Hence, Cartesian dualism was born. Thought, Descartes concluded, was of the mind, which pertained to the realm of the church. Everything not of the mind was delegated to the realm of the body and, therefore, to science. That unconscious processes could exist and exert their impact on our behavior was not even on Descartes’ radar.

The Medical Model

Descartes, as many philosophers and great thinkers, was a product of his times, but his ideas continue to live implicitly in our views of the world. As Dr. Joel Weinberger points out in our new book The Unconscious, we don’t sit at night, gazing at the stars thinking “I think, although I am unaware of doing so, therefore I am.”

The medical model has, I believe, inadvertently perpetuated the mind-body dualism. It is no more helpful to think of depression simply as a “chemical imbalance” as it is to view it as “something is wrong with my head.” Mind and body are interrelated, mutually-influencing, and inextricable. But it is simplistic to look at mental health as strictly biological either. No nutritionist or fitness expert will recommend that you eat more protein to build muscle, without also adding that you have to consistently exercise. It is similarly unlikely that a pill will “fix” depression, anxiety, or relationship problems without putting in consistent effort to identify, examine, and change well-rehearsed patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving.

Mind your Matter

Yet we know that “things of the mind,” as Descartes would say, can powerfully impact our physiology. For instance, a severe emotional stress response to trauma makes you 36% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease, like rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and psoriasis (Song et al., 2018). Treating stress-related psychological reactions, in turn, may help lower the risk of developing such conditions. And a recent article in The Atlantic discussed some of the growing literature on how traumatic events can alter our DNA, unknowingly impacting our children and even grandchildren.

The good news is that positive changes can also take place. Today, neuroimaging studies have found that psychotherapy of all modalities leads to changes in the brain, both at the functional and the molecular levels (see Hasse, 2011; Sankar et al., 2018). This is found to be true for the treatment of depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, specific phobias, and even Post-Traumatic Stress. In fact, recent studies suggest not only that PTS treatment changes the brain, but that through using imaging, we may be able to predict which treatment is most appropriate for whom. In other words, you are not only healing your mind through therapy. You’re also healing your brain. Maybe we cannot equate the two, but they certainly are not the discrete entities that Descartes argued.

The Moral

Perhaps it takes shocking headlines like Men’s Health’s recent “Not talking about mental health is literally killing men.” But we might as well be saying, “Not talking about mental health is literally making you sicker, increasing your chances of becoming immobilized, develop allergies, have a heart attack or a stroke, or make your children more susceptible to physical and mental illness without realizing it.”

So here is the action plan:

1. Do not let anyone shame you for doing something that is good for you. Be it tai chi in the park, drinking kale juice (I find the taste offensive but hey, if it works for you!), refusing to work a 70-hour week, or, yes, seeing a therapist. Stigma, stereotyping, and shaming thrive in an environment where we cannot own our experiences and claim our right to feel better.

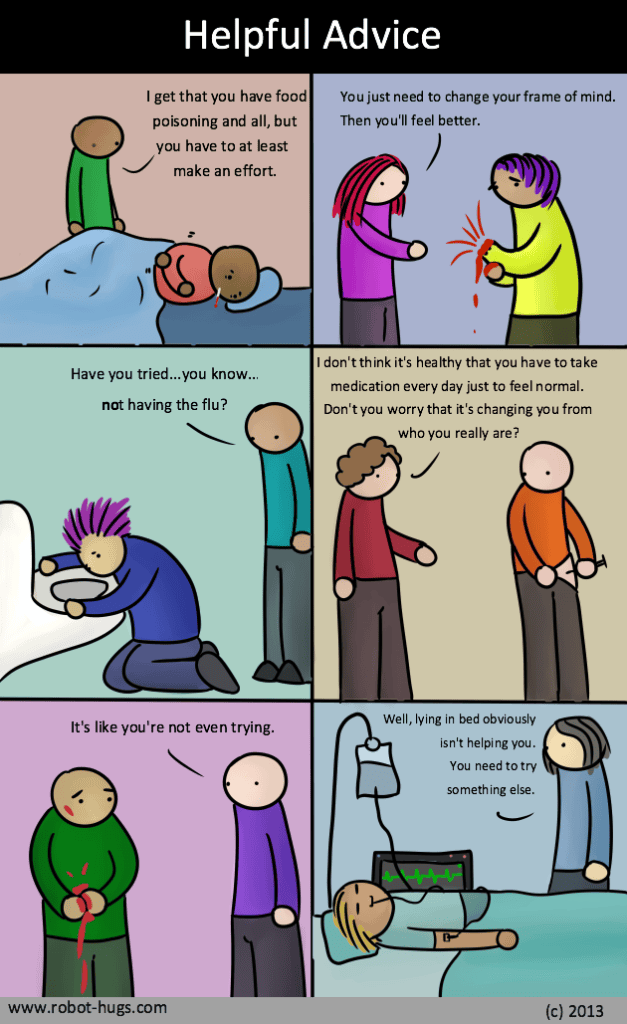

2. Conversely, stop shaming others. Driving over a bridge or hearing fireworks on the 4th of July may not be a problem for you. But if you react with “Get a grip” to someone who does have a problem, you are only silencing them. Unless we are finally, and proudly, able to say that something makes us anxious, sad, or even scared, we are simply sending the message that those words (and, hence, experiences) are unacceptable.

3. Educate yourself. Old habits die slow, but implicitly learned societal rules and biases take generations to uproot. Lucky for us, we have the internet and we can access gigabytes of knowledge on how mind and body are connected. A whole new field called embodied cognition studies this connection. (For example, did you know that if a stranger handed you a warm drink, you are more likely to rate them as a “warm” person, than if they handed you a cold soda? How is that for a connection between your physical experiences and social judgments?!

The bottom line is that we no longer use bloodletting to treat medical illness. Through scientific knowledge and advancements, we have learned to practice more effective ways of healing. In matters of the mind, we seem to be slacking in acknowledging what the evidence suggests – that mind and body are inextricably connected, and that we have to attend to the needs of both in order to be healthy. So, really, Descartes did the best he could with what resources he had. Are you?

References

Weinberger, J. & Stoycheva, V. (in press). The unconscious: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hasse, K., (2011). How psychotherapy changes the brain: Understanding the mechanisms. Psychiatric Times, 28(8).

Sankar, A., Melin, A., Lorenzetti, V., Horton, P., Costafreda, S., & Fu, C. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the neural correlates of psychological therapies in major depression. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 279(30), 31-39.

If you are interested in therapy for yourself or a loved one, you can request a free phone consult with one of our psychologists HERE or simply call us at 631-683-8499. All of our counselors at STEPS have made it our mission to expand our knowledge in trauma-informed care and provide the most expert, competent, and compassionate care to you and your family.

To subscribe to our Health News articles, so you can receive more like this one in your inbox, please go to our Home Page, and enter your email at the top of the page. Your subscription is strictly confidential!